Here's a pop quiz for all you media junkies: Which of the following took place in Ferguson, Missouri, recently, and which transpired during the 1968 Democratic National Convention (hint: both involved a certain higher-up with the last name Nixon):

- Two members of the media are quietly doing their jobs as a violent police action is under way. They are grabbed and assaulted by officers for no apparent reason.

- Peaceful protesters on a street are attacked by police with tear gas.

- A cop yells at a group of nonviolent protesters, "Bring it, you fucking animals, bring it!"

- A cop yells at a group of nonviolent protesters, "Run, you bastards, run!"

- In response to the violence, Nixon proclaims that the rule of law would be enforced and that there would be order.

- In response to the violence, Nixon proclaims that the county police need to stand down.

Ready with your answers? Nos. 1 and 2—the unprovoked assaults on reporters and protesters—are from both incidents. No. 3 was in Ferguson; No. 4 in Chicago. The fifth is related to Chicago, and are comments made by Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon. The sixth happened last week, as part of Missouri Governor Jay Nixon's response to the Ferguson nightmare.

What this country has just witnessed in Ferguson was, like in Chicago, an example of police gone wild—poorly led, poorly trained, unprofessional, displaying a complete lack of understanding of their jobs. It was an abomination that stains the reputation and credibility of talented, well-trained law enforcement officers throughout the country. It also adds to the danger these honorable men and women face, because the populace is increasingly afraid of their unfit brethren.

Of course, not 100 percent of the protesters in either Ferguson or Chicago were nonviolent and law-abiding but, as one federal agent told me, that is irrelevant. Police aren't permitted to burn down a peaceful family's home just because a guy down the street is beating his wife.

This disgrace has brought to the fore two major problems with modern law enforcement that have been allowed to simmer: first, the militarization of American police departments as a substitute for smart, proven but unsexy law enforcement techniques, and second, the growing awareness among African Americans that they and their children are in constant danger of being shot by cops because of institutionalized and subconscious racism. These are not independent issues.

Start with militarization. While this might seem like a "boys with toys" problem—cops playing dress-up as they search for their inner G.I. Joe—it's really about bad law enforcement tactics. One thing sometimes forgotten is that there are decades of research on policing tactics, and competent officers and their bosses rely on this research to guide them because they are want to maintain law and order, instead of just pretending the movie RoboCop was a documentary. Research shows that militarization rarely works, and usually makes things worse.

Studies also show that police have the power to either lessen the tensions of an angry group of people or goad them into a riot. This conclusion is based on the Elaborated Social Identity Model (ESIM), which is the leading scientific theory on managing a boisterous horde of people. What the ESIM shows is that an angry crowd can be driven to riot if they believe they are being treated unfairly—for example, by being confronted by cops decked out with military weaponry. When police treat a crowd justly and humanely, the chance of an uproar decreases and participants trust law enforcement more, the research shows.

When faced with a large-scale protest, police who understand their job know they must defend the free speech rights of participants with civility, while maintaining public safety. That means they protect both the protesters and other civilians. Confronting angry citizens in the garb of jack-booted thugs does plenty of damage and accomplishes nothing.

"Officers must avoid donning their hard gear as a first step,'' wrote Mike Masterson, chief of the Boise, Idaho police department, in an August 2012 report for the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Law Enforcement Bulletin. "Police should not rely solely on their equipment and tools. Experience shows that… dialogue is invaluable. Law enforcement officers must defuse confrontations to ensure strong ties with the community."

Adds Lieutenant Andrew Borrello with the San Gabriel, California, Police Department: "[Civility] represents self-disciplined behavior and patience with those who may not deserve it. Civility creates behavior that reduces conflict and stress.… "

For some of the best collections of studies on this topic, check out the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy at George Mason University. This group, which is consulted by law enforcement experts around the country, transforms much of the research on police tactics into a data matrix, showing in an easy to comprehend graphic which among more than 100 tactics and techniques have been shown to work, broken down by circumstances involving individuals, groups, small places, neighborhoods and jurisdiction. Not surprisingly, the most effective way to decrease crime and engender public support for law enforcement officers is through what is known as community policing and problem-oriented policing.

These approaches are the opposite of the swoop-and-crush approach taken early on in Ferguson—they entail having cops work closely with the community, become respected contributors to it, engage with both private and public organizations and do a lot of research—know their community. In other words, it's about making the police an appreciated participant in the daily life, rather than a threatening "other" enthralled with its authority, ego and weaponry.

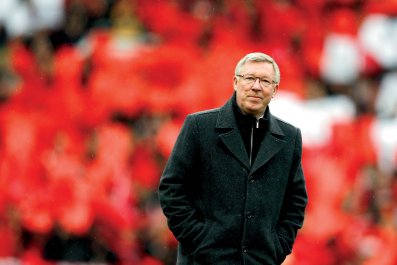

There is no better example of this than what happened in Ferguson. When the cops engaged in their war games, the streets turned into a battle zone. After Governor Nixon replaced the incompetent leadership and officers with a skilled commander and better trained cops, everything changed. Captain Ronald Johnson of Missouri State Highway Patrol appears to have learned about law enforcement techniques from research and professional conferences rather than from television cop shows.

Johnson's first day on the job—following a night of violent clashes between police and locals—he walked with protesters, hugged residents, assured them law enforcement was not there to intimidate them, and reassured citizens that everyone had the right to speak their minds. He ordered his officers not to use gas masks and, after a night of cops dressed like ninjas, made sure they wore standard uniforms. Then, he took the next important step: he told residents he would not tolerate anyone interfering with nonviolent protests, but that his officers also would not stand for looting. No doubt most of the residents agreed with him on that. He earned trust, and then made sure the peaceful residents were on his side about containing crime.

The result? A night of peaceful demonstrations, with no overwhelming police presence and no arrests. In one day, a smart cop defused one of the most dangerous police conflicts in recent memory.

Unfortunately, the next day, the original bumblers jumped back in for another quick demonstration of their incompetence. With tensions calming, Chief Thomas Jackson of the Ferguson Police decided to throw some gas on the embers by releasing video purporting to show the teenager who had been killed, Mike Brown, stealing some cigars from a convenience store. That gave Fox News and the like some new talking points, but the gratuitous victim-smearing set off a new night of confrontations.

Of course, the gentle approach isn't always the right choice. There is a place for heavy-duty equipment and tactics—a large-scale terrorist attack or a bank robbery by criminals wearing body armor and carrying automatic weapons come to mind—but these are exceedingly rare. When law enforcement succumbs to feverish paranoia and breaks out its high-powered arsenal, you get a debacle like Ferguson.

The perception among African-Americans is that they are more likely to be assaulted by cops than white citizens, and they are right. To understand why that is true, look at the evolution of police paramilitary units—often known as Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams. Between 1980 and 2000, the number of these paramilitary units exploded by 1,400 percent, to the point of absurdity. More than 80 percent of small town law enforcement agencies have SWAT teams; almost 90 percent in larger areas have them. This escalation would make sense if, say, there had been a boom in the number of hostage, sniper or terrorist situations. But America is not Iraq, and these types of incidents are no more common than they were in the 1980s. So, how to justify these unnecessary expenses? One way has been to call out the SWAT team even if the situation doesn't call for one.

Research by Professor Peter Kraska at Eastern Kentucky University shows that 80 percent of the paramilitary deployments by police departments were for "proactive" applications—in other words, instances of police-initiated violence rather than in response to an unusual threat. The majority of these involved "no-knock" and "quick-knock" raids on private homes, searching for contraband like drugs, guns or cash.

For more than a few poor minorities, there is no telling when a team of black-hooded strangers dressed in battle fatigues and military helmets will come crashing through their door in the middle of the night. By 2007, Kraska had recorded 275 instances of "seriously botched" SWAT raids on private homes, often resulting in civilians being killed under very questionable circumstances. And, according to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union, the majority of these unnecessary raids are inflicted on minorities—upward of 54 percent.

These types of actions subject everyone involved to unnecessary danger. In 2008, a SWAT team in Lima, Ohio broke down the front door of a rented home and opened fire, killing an African-American woman named Tarika Wilson as she held her 14-month-old son; Wilson had committed no crime and the police were looking for her boyfriend to serve a drug warrant.

In 2011, a SWAT team in Framingham, Massachusetts broke down the door of Eurie Stamps, a 68-year-old African-American grandfather of 12, and shot him; Stamps had committed no crime and the police were looking for his girlfriend's son, who not only didn't live in the house but was already in custody.

In 2010, a SWAT team in Detroit tossed a flash-bang grenade through a window into a living room where 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley Jones was sleeping, then crashed through the door and killed her with a single shot.

There is story after story of SWAT teams raiding the wrong house, or going after the wrong person, or using their grenades recklessly and killing people who were doing nothing more suspicious than sleeping or watching a ballgame on television.

When Sheriff Rick Fullmer of Marquette County in Wisconsin, disbanded his SWAT team in 1996, he said quite clearly that the superhero mentality was part of the problem: "Quite frankly,'' he said of his officers, "they get excited about dressing up in black and doing that kind of thing."

All of this aggression by some police agencies feeds into another concept that turns up in the research—when tactics like the unneeded use of paramilitary units become an accepted part of a department's operations, unnecessary violence can spread into the workaday policing performed by cops. A Justice Department investigation of the Albuquerque Police Department completed this year found that the overuse of SWAT, along with other factors, contributed to a culture of aggression that manifested itself in police routinely using excessive force—including shooting suspects dead when there was no imminent threat, and even Tasering a man who had poured gasoline on himself. He burst into flames.

According to government data, African-Americans make up 28 percent of all people arrested in this country. Yet data from the federal government's Bureau of Justice Statistics show that African-Americans account for 35 percent of all suspects killed during an arrest. In other words, an arrested African-American is more likely to be killed by police during an arrest than any other race. In fact, a review of officer-involved shootings in which one cop mistakes another for a perp shows that minority undercover officers have been killed significantly more often by colleagues than white ones. So, the reason minorities feel at greater risk of physical harm from the police is because they are at greater risk.

Studies on the role of race in decisions to use force are contradictory. Some long-term research involving controlled environments where test subjects are told to watch videos and press a button (to shoot) suggest that both police and civilians are more likely to "shoot" unarmed African-Americans in the videos than unarmed whites. However, other studies in similar controlled environments reveal that, while they make more mistakes across the board, police who are under pressure do not show a significant racial disparity in their shooting decisions. But while the social scientists debate the meaning of results in the lab, the shooting statistics consistently show that blacks face a greater threat from the police than whites do.

So what does this all mean? Too many police departments in America have lost their way, have become caught up in a sense of grandiosity that comes from misunderstanding their mission that is only exacerbated by their obsession with war toys. As Ferguson has demonstrated, there are plenty of incompetent police departments that give law enforcement a bad name because they have taken the shortcut of relying on armor and fatigues instead of research and community engagement.

The bottom line here is that police in this country have created a crisis in confidence, one that is worsened by every new story of an unarmed child cut down or an innocent person killed in a botched raid. Only the cops can fix this, by recognizing that more and better training is needed for a lot of these officers so they know their job is to protect the communities they serve, not terrify them.