Incidental collection in a manila envelope

Smith made little reference to the intelligence and surveillance abuses under previous administrations, dismissing them as mere “excesses that could not be condoned.” Instead, the attorney general explained that during the Carter era, Congress set up onerous “procedures governing virtually every aspect of intelligence gathering in the US or affecting US citizens abroad.” These included the pesky House and Senate Select Committees on Intelligence, FISA, and FISC. (In the subsequent decades, of course, FISC has been so secretive that it did not release its first public docket until after the initial Snowden revelations last year.)

“In summary, President Reagan inherited an intelligence community that had been demoralized and debilitated by six years of public disclosures, denunciation, and budgetary limitations,” Smith continued.

What pushed this administration to reach for more surveillance power? It was largely the threat of international terrorism and Soviet infiltration of the United States. Although Smith does not link the two explicitly in that speech, earlier that year the CIA had been strongly concerned with Soviet support of terrorism based on a May 1981 book called The Terror Network.

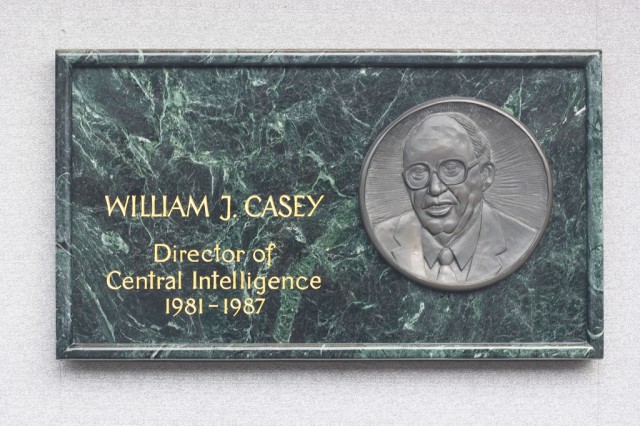

Casey was so persuaded by this book that two months later he ordered a Special National Intelligence Estimate entitled "Soviet Support for International Terrorism and Revolutionary Violence." But according to Goodman, the book and the government’s own rapid acceptance of the Soviet terrorism theory was entirely fraudulent. In fact, he said, it was black propaganda that the CIA created within the Soviet Union to stir up dissent. Goodman believes there was incidental collection on Americans happening left and right, and at the time it was easy to determine who the government was monitoring even if the name was obscured.

“12333 was designed to allow NSA to have greater latitude when they pick up Americans [as part of] targets overseas,” Goodman said.

For example, Goodman explained how the NSA targeted foreigners abroad, often in Latin America, as part of the global Soviet threat. In doing so, the NSA would incidentally collect information about, say, an American traveling in El Salvador in October 1981. One high-profile American who was traveling there at that time happened to be Sen. Christopher Dodd (D-CT), now the head of the Motion Picture Association of America.

“When I testified against Robert Gates [during confirmation hearings] in 1991, I brought that up, seeing intercepts that referred to American congressmen [and senators],” Goodman continued. “When those details arrived [to the CIA] in a brown manila envelope, they would scratch out the name, but you knew who was traveling at a particular time.”

EO 12333, still going strong

Binney is a more recent NSA veteran, retiring in 2001. He said that such practices continued even during his tenure.“There was a procedure called a ‘series check’ as to what to do with the name, should you redact it, and that depended on who it was and what they were doing and who you were going to tell,” he told Ars. “Those things were done because of incidental mentioning of someone’s name; that was pretty much set up and there was a process to go through. We were well aware of it at the time. I wasn’t in an area where I was too involved in any of that. But the techniques we used to fight the Soviet Union apply today.”

Despite using the same legal justification for this incidental collection today, the massive expansion of technological prowess since means that other intelligence veterans like Goodman are more concerned than ever about surveillance overreach.

“There would be no comparison to the capabilities of NSA now compared to three decades ago,” he said. “It’s proliferating all the time with their technology as to what they’re able to do.”

Ed Loomis, a cryptologist at the NSA from 1964 to October 2001 who later became a whistleblower, told Ars that every year, everyone working in the signals intelligence (SIGINT) division had to read EO 12333, FISA, and US SIGINT Directive 18 (July 1993) as a way to keep refreshed on the laws. Prior to the September 11 attacks, Loomis said the NSA's internal policy was to stay much more in line with FISA and not collect information—incidental or otherwise—on Americans.

In fact, Loomis initially wanted to use that same provision of EO 12333 (Section 2.3 paragraph C) on a temporary basis to conduct US-to-foreign and foreign-to-US collection. On September 14, 2001, he was brought into a meeting with NSA lawyers and other lawyers who were never identified—he thinks that one of them may have been David Addington, then-Vice President Dick Cheney's lawyer who crafted and controlled the legal documents drafted in the days after the attacks.

"It was the NSA lawyers that responded to that suggestion, and they said that that's not in conformance with FISA," Loomis told Ars. "I wasn't going to argue with them at that point, this was three days after 9/11, the whole world is shocked. Here I'm trying to get them to use something, to use a prevision that Reagan had put in place for extenuating circumstances, and they ignored it."

Loomis, Binney, and others were pushing a surveillance program known as ThinThread, which was discontinued weeks before the September 11 attacks. ThinThread supporters claim it had the ability to encrypt US persons' data so that analysts would not know who it was about. Prior to September 11, according to Loomis, the NSA's policy was that the FISA law trumped EO 12333, whereas after, it essentially became the other way around. (This is likely what Snowden was referring to in his internal query regarding the hierarchy of laws.)

"If I found a loophole, I wanted to exploit the loophole, which is why I wanted to use 12333 to do US-to-foreign and foreign-to-US. I wanted to push the lawyers as far as they would go," he continued. "My concern was the security of US persons as well as the privacy of US persons. I thought I had a means of protecting their identities through the encryption."

Loomis said that in general he does not support domestic surveillance and that he's bothered by how information was shared with the Drug Enforcement Agency, FBI, and perhaps even state police organizations. But, he said, "I trust NSA analysts because I've worked with them for 30 some-odd years and I know that with the exception of those that got fired over the LOVEINT thing that they have their hearts in the right areas. They would not intentionally go in and read US communications for jollies, but they are really dedicated to track foreign parties that are intent on doing us harm. So I trust them. The problem is that when the raw data gets shared with law enforcement communities, I've seen too many situations where they abuse it."

And this is where all the NSA veterans Ars spoke with agreed. No matter Reagan’s intent when expanding intelligence abilities, it’s simply a different era these days. New threats combined with better technologies have created an unfortunate situation.

“You have these technical capabilities, and they become more expansive, and you do them because you're capable,” Goodman said. “And when you have a threat perception, you usually can justify or rationalize anything you want to do.”

...but is EO 12333 the real problem?

Thomas Drake, another well-known NSA veteran turned whistleblower, put it in simpler terms. “12333 is now being used as the ‘legal justification.’"Drake spoke with Ars while on break from his job at the Apple Store in Bethesda, Maryland, just outside Washington, DC. He's held this post since leaving the NSA in 2008 while facing 10 felony counts of illegally taking classified information to his home, making false statements to investigators, and obstructing justice. In June 2011, after famously refusing to take a plea deal, Drake finally gave in. He pled guilty to a single misdemeanor count of exceeding his authorized access to government computers.

“It’s not technically law,” he continued. “An executive order is the equivalent of the law, we have a constitutional process by which laws are created in this country. When the details started coming out about the mass surveillance program, the government began to modify it under Bush, but they are using it as the final backstop in their defense: ‘The Program.’ Don’t let 12333 distract you; there’s a much larger authority that they’re desperate to protect."

“The Program” that Drake is referring to is the President’s Surveillance Program (PSP), which Ars has reported on previously. In the weeks after the first Snowden documents, a leaked classified draft report by the NSA’s Inspector General was published by The Guardian and The Washington Post. It explored the PSP's beginnings and evolution.

“The NSA has carte blanche on foreign intelligence,” Drake said. “They’re hiding behind 12333 to continue the vast collection of metadata and content. I’m just telling you that what’s enabling that is there’s a rule, a thing to understand, the government will never admit something that is still considered classified if it has not been fully disclosed in a way that they have to acknowledge it. As long as there is reasonable doubt, they will hide behind what has been disclosed. What has been disclosed is 12333.”

The PSP's legal justification was provided by a still highly classified document that President George W. Bush signed on October 4, 2001, entitled "Authorization for specified electronic surveillance activities during a limited period to detect and prevent acts of terrorism within the United States."

The authorization has never been published, but the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) unexpectedly acknowledged it as part of a declassification review in December 2013. According to that NSA Inspector General draft leaked in 2013, the NSA itself wasn’t even allowed to see the legal authorization for at least two years.

On May 6, 2004, the Office of Legal Counsel within the White House prepared a 74-page memo to the attorney general to outline the legality of “The Program.” The publicly released version has substantial redactions. It does, however, contain this noteworthy section:

The President has inherent constitutional authority as Commander in Chief and sole organ for the nation in foreign affairs to conduct warrantless surveillance of enemy forces for intelligence purposes to detect and disrupt armed attacks on the United States. Congress does not have the power to restrict the President's exercise of this authority.

The memo also specifically mentions a legal analysis of EO 12333 in a page that is almost entirely redacted.

According to the December 2013 document from the ODNI, this program is now governed under the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which remains law.

“That’s the problem,” Drake said. "That’s why you can’t have secret laws and secret orders in a constitutional order; it’s anathema. All of this was avoidable. We had the technology and the laws in place. We didn’t have to upend anything. No one has been charged for violating FISA. Those who have tried to expose it were charged with espionage, like me. The government has unchained itself from the constitution.”

Earlier this month, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board said it would re-examine EO 12333 after all the fanfare. But based on history, overturning an executive order simply isn't a common outcome. Unless done by a subsequent executive order, it's extremely difficult and has rarely happened. So for now, American data remains as accessible as it's ever been.

reader comments

114