Marie Kondo and the Privilege of Clutter

The Japanese author’s guide to “tidying up” promises joy in a minimalist life. For many, though, particularly the children of refugees and other immigrants, it may not be so simple.

At every wedding I’ve been to this past year, the event space has been decorated with family portraits—black-and-white photos of grandmothers and grandfathers, pictures of parents with giant smiles and ‘70s hairstyles. Meanwhile, the bride and groom wear family relics and heirlooms: jewelry passed from mother to daughter, cufflinks and ties passed from father to son.

As a child I used to cry when looking at those kinds of photos and mementos. But it wasn’t until this past summer when I was planning my own wedding that I understood just why these kinds of items inspired so many complicated feelings. When my now-husband asked if we wanted to make a slideshow of our family photos for our own wedding, I realized we barely had any. Both my grandmother and grandfather emigrated from Poland to Cuba in the years preceding the Holocaust: my grandmother by boat with her mother in 1930 when she was 8 years old, and my grandfather in 1937, at the age of 18. They fell in love with each other and the country that took them in, even as they grieved the family members who didn’t make it out alive.

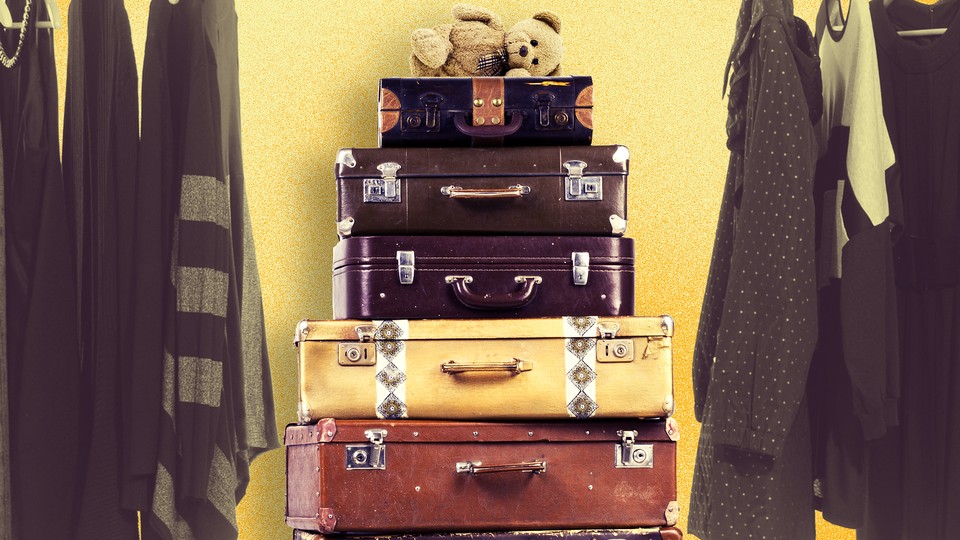

After Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, their lives changed once more. Their small store was closed for periods of time by the government (the boards covering their storefront were frequently graffitied with threatening swastikas, a sign that they may not have entirely escaped the frightening environment they tried to leave in Europe). As the revolution began, material comforts began to disappear. Eventually, their business and home were both shut down by the Cuban government and, in 1968, my grandparents, mother, and aunt came to the U.S., leaving everything but a few pieces of clothing behind.

In the U.S,. my grandparents and mother responded to the trauma they’d experienced by holding on to things. My grandfather was a collector who was prone to hoarding. He’d often find random trinkets on the street and bring them home, and he kept everything, from books to receipts to costume jewelry. My grandmother and my mother were more practical, saving and storing canned foods, socks, and pantyhose. In my home, we didn’t throw out food or plastic bags, or clothing that was out of style but that still fit us. We saved everything.

Today, when my mother comes to visit she still brings bags full of useful items, from Goya beans to cans of tuna fish and coffee: things she knows will last us for months and months. It doesn’t matter if I tell her we just went to the store, or that we have plenty of food, or that I don’t need any more socks or underwear. A full pantry, a house stocked with usable objects, is the ultimate expression of love.

As a girl growing up in the U.S., I was often exhausted by this proliferation of items—by what seemed to me to be an old-world expression of maternal love. Like many who are privileged enough to not have to worry about having basic things, I tend to idolize the opposite—the empty spaces of yoga studios, the delightful feeling of sorting through a pile of stuff that I can discard. I’m not alone in appreciating the lightness and freedom of a minimalist lifestyle. The KonMari method, a popular practical philosophy for de-cluttering your home, has tapped into a major cultural zeitgeist.

Since the Japanese “professional organizer” Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up was released in 2014, it’s become a New York Times bestseller and sold over 3 million copies. Kondo’s tips on de-cluttering have been featured everywhere from The Today Show to Real Simple to The Guardian, and have inspired the follow-ups Spark Joy, an illustrated guide to tidying things up even more, and Life-Changing Magic, a journal where you can ruminate on the pleasures of owning only your most cherished personal belongings.

At its heart, the KonMari method is a quest for purity. To Kondo, living your life surrounded by unnecessary items is “undisciplined,” while a well-tidied house filled with only the barest essentials is the ultimate sign of personal fulfillment. Kondo’s method involves going through all the things you own to determine whether or not they inspire feelings of joy. If something doesn’t immediately provoke a sense of happiness and contentment, you should get rid of it.

Kondo seems suspicious of the idea that our relationship with items might change over time. She instructs her readers to get rid of books we never finished, and clothes we only wore once or twice. She warns us not to give our precious things to our family and friends, unless they expressly ask for them. She’s especially skeptical of items that have sentimental value. In her first book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Kondo says,

Just as the word implies, mementos are reminders of a time when these items gave us joy. The thought of disposing them sparks the fear that we’ll lose those precious memories along with them. But you don’t need to worry. Truly precious memories will never vanish even if you discard the objects associated with them … No matter how wonderful things used to be, we cannot live in the past. The joy and excitement we feel in the here and now are most important.

Throughout Spark Joy, Kondo includes adorable minimalist drawings of happily organized bathrooms, kitchens and closets. Sometimes she even includes drawings of anthropomorphized forest animals lovingly placing items into drawers using the KonMari method.

Kondo is unfailingly earnest in her assertion that the first step to having a joyful life is through mindful consideration of your possessions. Emotions throughout both of her books are presented as being as simple as her drawings. You either feel pure love for an object or you let it go. But beneath some of the self-help-inspired platitudes about how personally enriched you’ll feel after you’ve discarded items you don’t need, there’s an underlying tone of judgment about the emotional wellbeing of those who submit to living in clutter. Those who live in KonMari homes are presented as being more disciplined: invulnerable to the throes of nostalgia, impervious to the temptation of looking back at something that provokes mixed feelings.

Though an article on Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness website Goop claims that American culture is the embodiment of excess, it’s pretty clear to me why the KonMari Method has caught on in the U.S. A recurring emphasis on self-improvement and an obsession with restriction can be found in everything from diet trends (where we learn to cut calories in order to be smaller and less encumbered by literal weight), to the consumer culture fixation with replacing old things that no longer provide joy with new, “improved” things that will.

For affluent Americans who’ve never wanted for anything, Kondo sells an elegant fantasy of paring back and scaling down at a time when simplicity is a hot trend. The tiny-house movement, for example, urges consumers to eschew McMansion- style houses for the adorably twee simplicity of a 250-square-foot home.

Of course, in order to feel comfortable throwing out all your old socks and handbags, you have to feel pretty confident that you can easily get new ones. Embracing a minimalist lifestyle is an act of trust. For a refugee, that trust has not yet been earned. The idea that going through items cheerfully evaluating whether or not objects inspire happiness is fraught for a family like mine, for whom cherished items have historically been taken away. For my grandparents, the question wasn’t whether an item sparked joy, but whether it was necessary for their survival. In America, that obsession transformed into a love for all items, whether or not they were valuable in a financial or emotional sense. If our life is made from the objects we collect over time, then surely our very sense of who we are is dependent upon the things we carry.

It’s particularly ironic that the KonMari method has taken hold now, during a major refugee crisis, when the news constantly shows scenes of people fleeing their homes and everything they have. A Vice article, “All the Stuff Syrian Refugees Leave Behind During Their Journey to Europe” shows discarded things ranging from trash to toys to ticket stubs. Each items looks lonely and lost: like evidence of a life left behind. For a project titled “The Most Important Thing,” the photographer Brian Sokol asks refugees to show him the most important thing they kept from the place they left behind. The items they proffer range from the necessary (crutches), to the practical (a sewing machine), to the deeply sentimental (photographs of someone deeply loved, treasured instruments, family pets).

Against this backdrop, Kondo’s advice to live in the moment and discard the things you don’t need seems to ignore some important truths about what it means to be human. It’s easy to see the items we own as oppressive when we can so easily buy new ones. That we can only guess at the things we’ll need in the future and that we don’t always know how deeply we love something until it’s gone.

In this way, I was built for the KonMari method in a way my mother never was. I grew up in a middle-class American home. While we were never wealthy, we also never truly wanted for material things. As an adolescent, I would tell my mother that I was an American, and that, as an American, I didn’t have to be loyal to anything or anyone if I didn’t want to. I’d throw away the last dregs of shampoo or toothpaste, which my mom would painstakingly rescue from the trash before scolding me for being so wasteful. I’d happily throw out or donate clothing I didn’t want any more.

My quick disposal of things always made my mother irreparably sad. She mourned the loss of my prom dress (which I gave to a friend) and the pots and pans she gave me for college (which I left in the group house I lived in), and she looked horrified when I once dumped a bunch of letters from friends and family in the trash. For me, being able to dispose of things has always been one of the ways I learned to identify as an American—a way to try and separate myself from the weight of growing up in a home where the important things that defined my family had long been lost.

To my mother, the KonMari method isn’t joyful; it’s cold. “Americans love throwing things away,” she tells me, “And yet they are fascinated by the way that Cubans have maintained their houses, their cars. Yes, growing up we took great pleasure in preserving things. But we also didn’t really have a choice.”

Today, of course, my mother has plenty of choices, but throwing things away still makes her anxious. Now that my grandparents have both passed away, my mother still struggles to decide what to do with all that stuff. It’s very painful for her, and my father’s encouragement that she sift through everything, organize it in some kind of clearly delineated way, often falls on deaf ears.

A few months ago, when I was visiting home, my father asked if I would help go through some of the items. Now that he and my mom are older and my brother and I are grown, they’ve both expressed a desire to downsize. In the car, my dad recommended starting with my childhood bedroom, which looks exactly as it did when I was 14 years old, pink and purple, filled with childhood books and stuffed animals, half-filled journals, and never worn shoes. At first I was enthusiastic about the project. “We can give a lot of those things to charity,” I said.

But at home, I sat in front of my bookshelf and did exactly what Kondo cautions most against: I started my project of decluttering by going through the things that mattered most to me: the books I loved when I was a child; the CDs made by dear friends and stacked high in no particular order; the college textbooks I never remembered to return. Objects imbued with memories of a person I once was, and a person that part of me always will be.

I didn’t want to give any of it up.

Kondo says that we can appreciate the objects we used to love deeply just by saying goodbye to them. But for families that have experienced giving their dearest possessions up unwillingly, “putting things in order” is never going to be as simple as throwing things away. Everything they manage to hold onto matters deeply. Everything is confirmation they survived.