How Apple Sells its Controlling Ways as Futurism

The company’s controversial design choices make it hard to imagine the alternatives they preclude.

“Our lightest product ever,” the page announces. Lithe and sleek like all Apple’s wares, the Apple Plug is a small, aluminum stopper meant to seal up the “archaic headphone connector” in your iPhone 6 or 6s. Machine-rounded at the end to match the device’s curve, it comes in gold, rose gold, and space gray to match every iPhone finish. Once installed, the Apple Plug is eternal, permanently barring access to the 3.5mm port—which Apple just “courageously” removed from the new iPhone 7. Until you can get your hands on one, what better way to prepare for that bold future than to stop-up the temptation to live in the past?

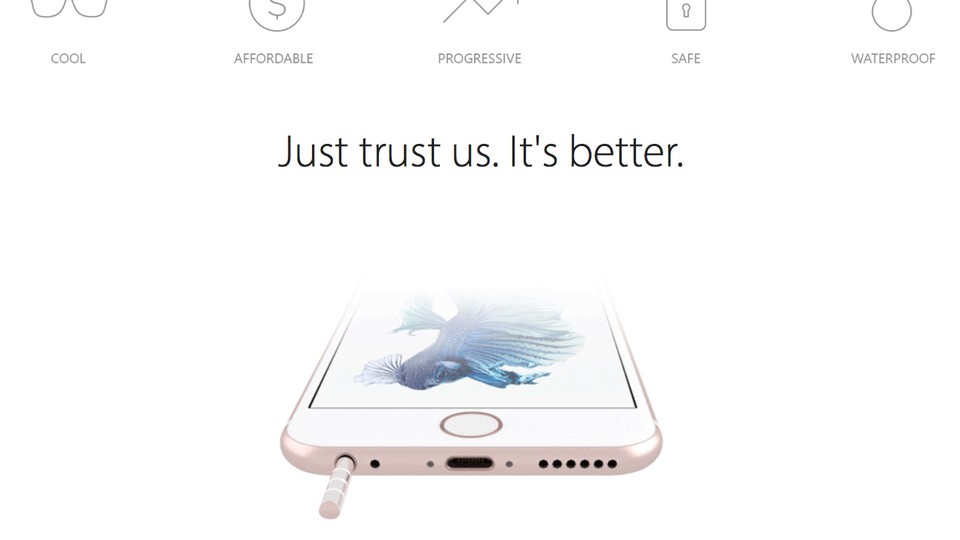

As you might have guessed, Apple Plug is a joke. Created by a South Carolina design studio called Nicer, the website is so dead-on in its visual design and copy, it’s easy to mistake for the real thing. Apple Plug sounds almost reasonable, even: “When we made iPhone 6 and 6s,” the text reads, “the world wasn't ready for the future. Now, it is. Apple Plug is the perfect solution.” Before affirming that it’s all a gag, a heading implores, “Just trust us. It’s better.”

As my colleague Kaveh Waddell explains, Apple portrays the removal of a century-old standard like the analog audio port as the ongoing expression of the company’s bold and unrelenting nature. Faced with a choice between abandoning the past with discomfort and embracing—nay, creating—the future, Apple chooses progress. Anyone who might complain is simply stuck in the past.

The company has a good track record for success, too. Two of its other forced obsolescences have largely been forgotten by today’s users. The removal of floppy drives upon the launch of the iMac in 1998 felt similarly aggressive at the time. Most computer users had dozens of disks loaded with software and files, all rendered useless. And the MacBook Air, first introduced in 2008, removed the optical drive to allow for a thinner, lighter laptop body. Today, none of Apple’s computers feature built-in CD/DVD drives, and nobody seems terribly bothered. Thinner computers are far more important.

But Nicer’s parody underscores an unseen motivation: Apple’s aggressive battle against the retrograde pull of hardware standards also exerts an implicit control on its users. Buying an Apple product becomes an exercise in trust for the future it will bring about. And the problem with the future is that it’s very hard to think about how it might have been different once it arrives.

* * *

When the iMac came on the scene, floppy disks were already insufficient to carry the increasingly bloated files produced by computer use. The CD-ROM drive had been delivering multimedia content for half a decade already, and big graphics files were commonplace well beyond the domain of graphic design and publishing that had been Mac mainstays since the 1980s. External, high-capacity floppy disk storage had been around for some time, but Iomega’s 1994 Zip drive, with its 100 MB disks, had become the standard for those who needed to move more than a high-density floppy’s 1.44 MB of data around. In 1996, the Universal Serial Bus (USB) connection standard had also emerged, allowing easier, cheaper attachment of peripherals, among them external disks and, later, flash drives. And of course, the internet was becoming popular beyond universities and research labs, offering access to network storage and transfer of files large and small.

But the ordinary home computer user—the target of Steve Jobs’s bold new entry-level iMac—was less likely to see external drives, FTP, and even email attachments as obvious solutions to the problem of file creation and management.

If anything, the iMac suggested that computers weren’t tools with which to generate things that left those computers. The first models came with a CD-ROM drive, but writeable optical drives didn’t appear until 2001. The iMac was a fun, colorful, and self-contained unit of computer experience. It purposely eschewed disturbance from without. A 1998 television spot for the machine overlaid the sound of traffic as it panned over a boring, complex PC before giving way to the calming chirp of birds as the iMac came into view.

With iMac, Apple began to shift computers from their role as tools with which to make materials for work and play, to a device with which to view previously-created media. In 1977, Apple had touted the fact that its first computer would let users “start writing your own programs the first evening.” By 1999, iMac print ads boasted, “The thrill of surfing. The agony of choosing a color.” The computer was already becoming the device that the iPhone and iPad would later realize: fashion-forward digital media distribution endpoints, rather than utilitarian machines for creating materials for use or output in other contexts.

By the time a CD-RW drive arrived in the iMac, Apple had released another new product: the iPod. Just when CDs became viable—if single-use—tools for data storage, Apple flipped the medium’s obvious use on its head: just a way to get content onto another, smaller handheld computer. Even today, when people create things with computers, they tend to do so inside the walled gardens of apps, social networks, and other online services.

The retirement of the optical drive also had implications that were harder to see at the time, not to mention unrelated to the stated purpose of thinness and lightness. A decade ago, software, music, and movies were still frequently distributed on optical disks. Thanks to standards like CD, DVD, and Blu-Ray, that meant that anyone could make such media. And once someone took possession of a physical disk, it could be used over and over again with compatible hardware. It was owned and therefore could be resold, lent, or donated. The result was a diversity of creative contexts and distribution channels, along with a natural means for archival and preservation.

But once the optical disk became an optional accessory, the stage was set to move all media and software distribution to online services. iTunes had been selling music online since 2003. Netflix had just begun streaming movies and television on demand in 2007. Apple had just launched the iOS App Store in 2008, and the Mac App Store followed in early 2011. The company reviews and approves (or declines) every title that appears on the storefront.

In 2012, Apple introduced Gatekeeper, a security feature of the Mac’s operating system that, in its default setting, prevents users from running software that hasn’t been distributed via the App Store or code-signed by an Apple-registered developer (a privilege that costs $99 per year). Created to limit the spread of malware, Gatekeeper has the side-effect of making it difficult to run programs that Apple hasn’t explicitly authorized as legitimate. It’s still possible to distribute programs by direct download (or by flash drive), of course, but the more app store proliferated, the less obvious and trustworthy such methods become.

And simultaneously, those apps become ever more evanescent. Thanks to the frequent updates required to move profitable iPhones, the App Store is littered with old software that doesn’t work. Some of it is abandoned, but others couldn’t find viable businesses on a platform that pushed prices down to zero, even as software and hardware updates made constant maintenance obligatory. Last week, Apple quietly notified developers that it would begin testing and removing apps that are non-functional or “outdated.”

* * *

It would be ridiculous—and it would give Apple too much credit—to imply that the company planned some elaborate conspiracy in 1998 or 2008 or even 2016 to control its users’ thoughts and ideas in the near- and far-future. The floppy disk’s removal didn’t cause the transformation of computers into consumption devices. Likewise, the optical disk’s disappearance didn’t underwrite the rise of top-down streaming services and centralized app stores and subscription-facilitated downloads.

But those choices did amplify the tendencies that were already present, giving them room to mature and to naturalize. When a desktop computer precludes local file storage and transfer, who wouldn’t settle comfortably into the wilderness of the web? When all software comes from App Stores, who would even think about the idea of making something distributable by other means? When using a smartwatch or a car stereo requires owning a compatible iPhone to drive it, who wouldn’t shrug that they already own one, anyway?

Today, it’s easy to ask if removing the headphone jack from iPhones is a futurist or a hostile choice. But history shows us why that question isn’t the right one. Removing the floppy and optical disk also seemed hostile, to varying degrees, in 1998 and 2008. But today, we can’t even remember that hostility, let alone muster any of it back. Apple’s influence and success has seen its design choices colonize competing products and services, from Android to Windows. The future that those choices helped create has become our present. Second nature. It’s hard to imagine an alternative.

The Apple Plug parody poses a different question: What are the implications of trusting Apple with the future, this time or any time? Thin MacBooks and swank iPhones sure do feel great. But what is the cost of having trusted Apple? What else might have come to pass instead? And what alternatives might yet be possible? Questions to answer in your next podcast, perhaps. Provided Apple’s future services still allow your audience to listen to it.