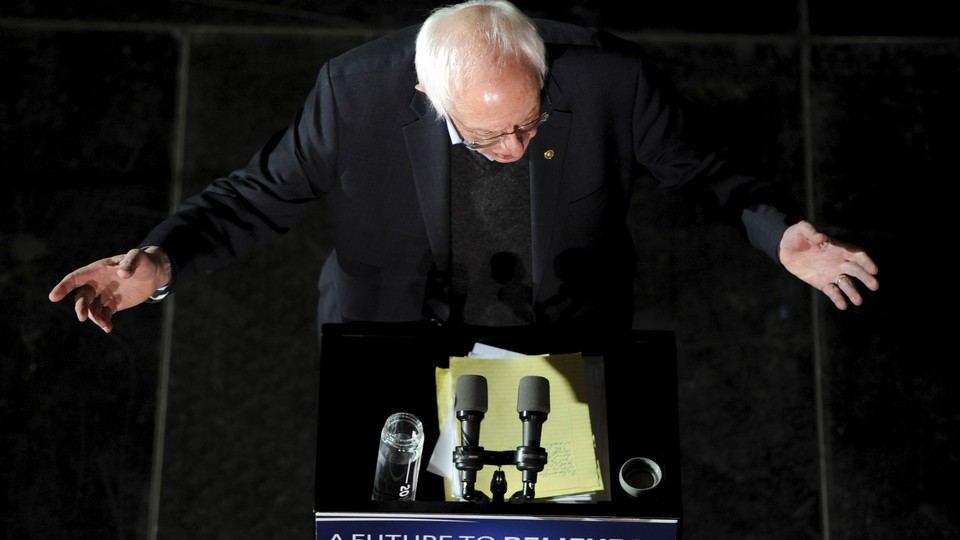

Bernie Sanders and the Liberal Imagination

What is doable and what is morally correct are not always the same things.

Last week I critiqued Bernie Sanders for dismissing reparations specifically, and for offering up a series of moderate anti-racist solutions, in general. Some felt it was unfair to single out Sanders given that, on reparations, Sanders’s chief opponent Hillary Clinton holds the same position. This argument proposes that we abandon the convention of judging our candidates by their chosen name:

Youth unemployment for African American kids is 51 percent. We have more people in jail than any other country. So yes, count me as a radical. I want to invest in jobs and education for our young people rather than jails and incarceration.

When a candidate points to high unemployment among black youth, as well as high incarceration rates, and then dubs himself a radical, it seems prudent to ask what radical anti-racist policies that candidate actually embraces. Hillary Clinton has no interest in being labeled radical, left-wing, or even liberal. Thus announcing that Clinton doesn’t support reparations is akin to announcing that Ted Cruz doesn’t support a woman’s right to choose. The position is certainly wrong. But it is hardly a surprise, and doesn't run counter to the candidate’s chosen name.

What candidates name themselves is generally believed to be important. Many Sanders supporters, for instance, correctly point out that Clinton handprints are all over America’s sprawling carceral state. I agree with them and have said so at length. Voters, and black voters particularly, should never forget that Bill Clinton passed arguably the most immoral “anti-crime” bill in American history, and that Hillary Clinton aided its passage through her invocation of the super-predator myth. A defense of Clinton rooted in the claim that “Jeb Bush held the same position” would not be exculpatory. (“Law and order conservative embraces law and order” would surprise no one.) That is because the anger over the Clintons’ actions isn’t simply based on their having been wrong, but on their craven embrace of law and order Republicanism in the Democratic Party’s name.

One does not find anything as damaging as the carceral state in the Sanders platform, but the dissonance between name and action is the same. Sanders’s basic approach is to ameliorate the effects of racism through broad, mostly class-based policies—doubling the minimum wage, offering single-payer health-care, delivering free higher education. This is the same “A rising tide lifts all boats” thinking that has dominated Democratic anti-racist policy for a generation. Sanders proposes to intensify this approach. But Sanders’s actual approach is really no different than President Obama’s. I have repeatedly stated my problem with the “rising tide” philosophy when embraced by Obama and liberals in general. (See here, here, here, and here.) Again, briefly, treating a racist injury solely with class-based remedies is like treating a gunshot wound solely with bandages. The bandages help, but they will not suffice.

There is no need to be theoretical about this. Across Europe, the kind of robust welfare state Sanders supports—higher minimum wage, single-payer health-care, low-cost higher education—has been embraced. Have these policies vanquished racism? Or has race become another rubric for asserting who should benefit from the state’s largesse and who should not? And if class-based policy alone is insufficient to banish racism in Europe, why would it prove to be sufficient in a country founded on white supremacy? And if it is not sufficient, what does it mean that even on the left wing of the Democratic party, the consideration of radical, directly anti-racist solutions has disappeared? And if radical, directly anti-racist remedies have disappeared from the left-wing of the Democratic Party, by what right does one expect them to appear in the platform of an avowed moderate like Clinton?

Here is the great challenge of liberal policy in America: We now know that for every dollar of wealth white families have, black families have a nickel. We know that being middle class does not immunize black families from exploitation in the way that it immunizes white families. We know that black families making $100,000 a year tend to live in the same kind of neighborhoods as white families making $30,000 a year. We know that in a city like Chicago, the wealthiest black neighborhood has an incarceration rate many times worse than the poorest white neighborhood. This is not a class divide, but a racist divide. Mainstream liberal policy proposes to address this divide without actually targeting it, to solve a problem through category error. That a mainstream Democrat like Hillary Clinton embraces mainstream liberal policy is unsurprising. Clinton has no interest in expanding the Overton window. She simply hopes to slide through it.

But I thought #FeelTheBern meant something more than this. I thought that Bernie Sanders, the candidate of single-payer health insurance, of the dissolution of big banks, of free higher education, was interested both in being elected and in advancing the debate beyond his own candidacy. I thought the importance of Sanders’s call for free tuition at public universities lay not just in telling citizens that which is actually workable, but in showing them that which we must struggle to make workable. I thought Sanders’s campaign might remind Americans that what is imminently doable and what is morally correct are not always the same things, and while actualizing the former we can’t lose sight of the latter.

A Democratic candidate who offers class-based remedies to address racist plunder because that is what is imminently doable, because all we have are bandages, is doing the best he can. A Democratic candidate who claims that such remedies are sufficient, who makes a virtue of bandaging, has forgotten the world that should, and must, be. Effectively he answers the trenchant problem of white supremacy by claiming “something something socialism, and then a miracle occurs.”

No. Fifteen years ago we watched a candidate elevate class above all. And now we see that same candidate invoking class to deliver another blow to affirmative action. And that is only the latest instance of populism failing black people.

The left, above all, should know better than this. When Sanders dismisses reparations because they are “divisive” he puts himself in poor company. “Divisive” is how Joe Lieberman swatted away his interlocutors. “Divisive” is how the media dismissed the public option. “Divisive” is what Hillary Clinton is calling Sanders’s single-payer platform right now.

So “divisive” was Abraham Lincoln’s embrace of abolition that it got him shot in the head. So “divisive” was Lyndon Johnson’s embrace of civil rights that it fractured the Democratic Party. So “divisive” was Ulysses S. Grant’s defense of black civil rights and war upon the Klan, that American historians spent the better part of a century destroying his reputation. So “divisive” was Martin Luther King Jr. that his own government bugged him, harassed him, and demonized him until he was dead. And now, in our time, politicians tout their proximity to that same King, and dismiss the completion of his work—the full pursuit of equality—as “divisive.” The point is not that reparations is not divisive. The point is that anti-racism is always divisive. A left radicalism that makes Clintonism its standard for anti-racism—fully knowing it could never do such a thing in the realm of labor, for instance—has embraced evasion.

This, too, leaves us in poor company. “Hillary Clinton is against reparations, too” does not differ from, “What about black-on-black crime?” That Clinton doesn’t support reparations is an actual problem, much like high murder rates in black communities are actual problems. But neither of these are actual answers to the questions being asked. It is not wrong to ask about high murder rates in black communities. But when the question is furnished as an answer for police violence, it is evasion. It is not wrong to ask why mainstream Democrats don’t support reparations. But when the question is asked to defend a radical Democrat’s lack of support, it is avoidance.

The need for so many (although not all) of Sanders’s supporters to deflect the question, to speak of Hillary Clinton instead of directly assessing whether Sanders’s position is consistent, intelligent, and moral hints at something terrible and unsaid. The terribleness is this: To destroy white supremacy we must commit ourselves to the promotion of unpopular policy. To commit ourselves solely to the promotion of popular policy means making peace with white supremacy.

But hope still lies in the imagined thing. Liberals have dared to believe in the seemingly impossible—a socialist presiding over the most capitalist nation to ever exist. If the liberal imagination is so grand as to assert this new American reality, why when confronting racism, presumably a mere adjunct of class, should it suddenly come up shaky? Is shy incrementalism really the lesson of this fortuitous outburst of Vermont radicalism? Or is it that constraining the political imagination, too, constrains the possible? If we can be inspired to directly address class in such radical ways, why should we allow our imaginative powers to end there?

These and other questions were recently put to Sanders. His answer was underwhelming. It does not have to be this way. One could imagine a candidate asserting the worth of reparations, the worth of John Conyers H.R. 40, while also correctly noting the present lack of working coalition. What should be unimaginable is defaulting to the standard of Clintonism, of “Yes, but she’s against it, too.” A left radicalism that fails to debate its own standards, that counsels misdirection, that preaches avoidance, is really just a radicalism of convenience.