One of the impressive feats accomplished by ILM for Rogue One is segueing from this ‘new film’ (made with advanced VFX techniques) into A New Hope (released, of course, in 1977, at a time when effects were done with models and motion control and optical compositing).

To make that happen, a special ops team at the studio studied the look of the ILM’s old-school work and researched what made and the stop-motion, motion control and other animation ‘feel’ so real, and how the modern CG techniques might be used to reflect that feel. All the while, ILM still capitalised on the advancements that the studio has pioneered in visual effects since the release of A New Hope.

Rogue One’s animation supervisor Hal Hickel recounts to vfxblog how that approach impacted his work for some of the specific sequences in the film, including the beach assault Walkers shots and the space battle.

vfxblog: It seemed like there was such a great opportunity to revisit classic things that we’ve seen in the other films that were done perhaps with stop motion or motion control back then. Can you talk about going back in time to animate say the Walkers that are part of that beach assault, for example, and retain their spirit?

Hal Hickel: That was super fun, I was really excited to do that. I know Phil Tippett and I revere his work and have done since I first saw Empire Strikes Back, or even Star Wars. So it was very important to me that we got those guys right. We made our Walkers a little different from the ones in Empire. These are meant to be cargo AT-ATs, and so I guess they’re AT-ACTs is what we ended up calling them. Their legs are a bit longer, the proportions are subtlety different, but for all intents and purposes they look very much like the Walkers in Empire. This was something I sort of peeled off for myself as my own little thing because as supervisor I don’t get as much opportunity to animate shots, things get too busy and I have to delegate that to my animators, but in this case I took this as my own little side project. And I studied footage from both Empire and Jedi of Walkers and I began by copying that pretty closely in terms of timing and feel.

But one thing we discovered is that for Rogue One, maybe because they’re a little taller and longer-legged, it looked better if we slowed them down slightly. So we did that, but other than that the timing of the steps and the way the body moves and everything is really taken pretty straight from what Phil and John Berg and those guys did on Empire. And as a side project to this, Dennis Muren and some other folks here at ILM had embarked on a little exercise to find out what is it about the original films and models and things like that that appeal to people so much? What can we take from the look of old school visual effects and what should we leave behind?

Part of that was to take some shots from the Original Trilogy and space shots of star destroyers, things like that, but also there was a shot of the Walkers, and then put CG versions into those shots to mimic as closely as possible in CG what you’re seeing in the original footage, in the original practical model versions, so we could figure out what things to take from the old look of things and what to leave behind.

So anyway, so that was interesting for me to look at as well, and helpful. So I animated a cycle for the Walkers that got used around a lot in most of the shots and then the animators, the individual animators took on specific shots of them blowing up or firing on our heroes or stomping on trees or whatnot.

vfxblog: There’s one shot of the Walker that received a lot of attention in the trailers and that was when it’s hit with a rocket propelled grenade and it’s head does a bit of a double-take. Can you tell me about that in particular because it is very memorable?

Hal Hickel: That was a sequence that got delivered to us pretty early on and stayed pretty much as it was all the way through, because obviously there were some changes to the action on the beach which people are well aware of because there are plenty of shots from the various trailers that are no longer in the film. But that was one beat that always stayed in and was great, and there were a lot of things to play around with there to get just right in terms of, you know he hits it, and then you think, oh has he damaged it?

And then there’s a beat, and then the head kind of swings back, and it’s really meant to be one of those moments like when the guy punches Arnold in Terminator and he just does that slow head turn back to the guy and you sort of know you’re in trouble, and it was really meant to be that kind of moment. But when you’re doing it with an AT-AT, you know, you’ve gotta play around with the timing a lot to make sure it feels like the right idea.

And then there was a lot of discussion about how the X-Wings should blast it and where the shots should come from and where the X-Wings should come from. Should they come from behind it, or over it, or off to the right I think that’s what we ended up with. And you know it’s just a million little decisions like that to work out, but it was really a fun sequence and it’s a nice cheer moment. You know, obviously things get sort of grim towards the end of the movie, and so having a few moments to cheer and feel like there were little minor victories in there along the way you know it was pretty important and was fun to put in.

vfxblog: What about the challenges of the space battle? How do you make it conceivable and digestible on screen?

Hal Hickel: We had three main approaches to figuring out the different beats of the space battle. First was traditional previs that The Third Floor was doing for us over in London, and they were right close by Gareth during the part of the production where post production was in the UK. At a certain point it moved back here to California, but while it was still there Gareth was working closely with those folks. And then at a certain point that segued over to us, and my animation team both here in San Francisco and up in Vancouver mainly – I had teams in Singapore and London as well – but for the space battle it was mainly these two west coast studios San Francisco and Vancouver. So we took over a big chunk of that of envisioning shots or modifying existing pre-vis that didn’t suit the narrative anymore as it sort of evolved.

And then the third thing that we did that was really useful for Gareth, and we didn’t just use it in the space battle, we used it in a number of places, but Gareth’s shooting style is really interesting. When he’s shooting the actors he likes to have kind of immersive 360 degree sets that he can kind of point the camera anywhere in, and he’ll get the actors out there and they’ll start walking through the scene, and even through the first couple of actual takes for the scene he and any other camera operators, as Gareth is frequently manning one of the cameras himself, will be kind of walking through the scene and finding angles.

So they’ll be getting in the way of the actors in some cases or sort of crouching behind them and looking over their shoulders and peering around to find the good angles, and so by the third or fourth take things are really gelling. They’ve figured out what the good angles are and how they want to shoot the scene, and the actors are all warmed up and things really start to work by that point.

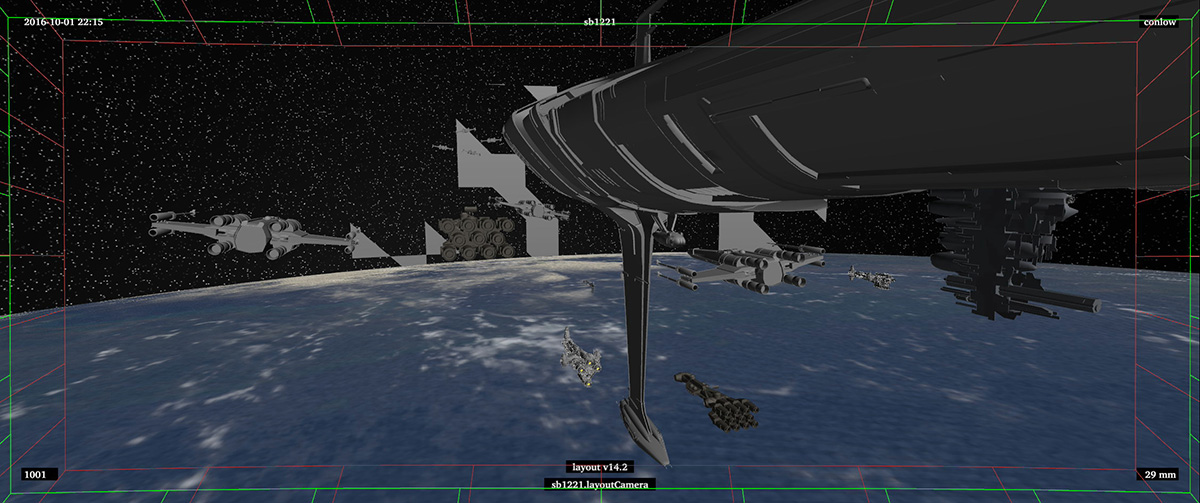

And so we wanted to figure out a way with all CG work, like space battle shots, to give Gareth the same opportunity. So what we did was we would pre-animate chunks of space battle action, or even a scene like when the Death Star dish is descending into its socket on the Death Star, and there are Imperial Star Destroyers floating around nearby, we set that up as a scene that we just loop. And it was a 3D scene like you’d find, you know we had it in a game engine in our system here on our motion capture stage.

Seeing a demo of the virtual camera that allowed Gareth Edwards to walk through and “shoot” battle scenes in #RogueOne. pic.twitter.com/ZQ5rIx5qBY

— Film School Rejects (@rejectnation) December 4, 2016

And Gareth would have a flat-panel display that was effectively his viewfinder, and it had different controls on the sides for picking different lenses and adjusting focus and all that kind of thing. And so he could walk through the scene as it was playing and find angles that suited him. And in fact those shots that we’ve seen a lot in the trailers of the shadow peeling back over the surface of the Star Destroyer, and then the following shot where the shadow is moving across the surface of the Death Star, and with the Star Destroyer out in front of it, that was something he found in that session. Because we had lighting and everything. So essentially it’s like you’re watching the scene that you’re standing in the middle of it in 3D, and you kind of look around and walk over next to one of the little floating star destroyers and kind of put your camera down next to it and frame up a shot with the Death Star in the background and compose the shot.

And so we used that, that was our third way of composing shots and developing space battle action was to sort of create these little mini-beats of action, and then have them looping and he could just sort of walk through them and find, you know, the good angles and shoot the scene that way. You’d get a rough version of the shot from that, and then we’d go through and clean it up and smooth it out. But the conception would come from him being able to just view it on the fly and improvise with the camera, which was great.

vfxblog: That side project of going in and checking how the miniatures could be translated to CG, was that something that was done with X-Wings and some of the space stuff as well?

Hal Hickel: Dennis and John Knoll and some other people who were involved with it chose a whole variety of shots of Star Destroyers and Millennium Falcon shots and one of the Walker shots, and just all across the Original Trilogy, and then they’d go in and like I said it might be a shot for instance of the Millennium Falcon flying through the asteroids, and then they might as an exercise put a second Millennium Falcon in the shot that was CG, and do one version where the idea is to match as perfectly as possible the look of the model Millennium Falcon that’s in the shot, and then do a second version where we kind of go alright, let’s do our modern version of it, and figure out what the middle ground is between the two.

And it was very instructive because we learned all kinds of things not just about matte lines or lighting or more obvious things you’d sort of expect, but we learned all kinds of things about how the ships moved and how the shots were designed based on the technology they had then and what it meant for, you know, how they would conceptualise a shot versus what we do now where it’s in 3D in the CG world and we can put the camera anywhere and there are no constraints, you know. It’s not a physical model on a pylon with the camera on a track and the track’s only so long and the camera lens will accommodate a certain angle view, et cetera. You know we don’t have those restrictions now and that creates, or contributes to a different aesthetic.

And so we’re studying what they’re doing, reverse engineering. And the great thing is we still have folks around here who worked on that. You know, Dennis himself worked on the original Star Wars trilogy, and Paul Huston is here and he worked on those films as well. And so it’s not like we have to guess at what those guys did back then. We know what they did and we know why the shots have the aesthetic that they do. And so it was kind of a good process to kind of revisit them and figure out alright, this stuff is very beloved, but you know it has a certain look that’s part of its time and how do we modernize it but preserve the things that people really dig about it?

A big part of it is making sure that our CG spaceships and whatever else we’re creating in CG, that it really has a physicality to it, a tactile sense – that’s one of the things with models is you always feel like in the back of your brain somewhere you kinda think yeah I know what that would feel like to put my hand on that. I think I know what that would feel like, what all those little bumps would feel like with that weathered paint you know that’s probably kind of, I think I know what that would feel like.

So that’s one of the things we struggle with with CG because none of it’s actually real. And the computer wants to make things very perfect and clean, and so we worked very hard in this film to make our models not feel like that.

For more on Hal Hickel’s work, here’s my article at Cartoon Brew about how ILM helped make K-2SO, the sassy security droid.