Strangers in Their Own Land

The psychological roots of liberals’ Trump depression—and what comes next

Every time Genevieve Caffrey hears the words President Trump, “I feel like I was physically punched in the stomach,” she says. “I feel like I’m in an alternative universe that was imagined and made fun of by late-night comedians before the election.”

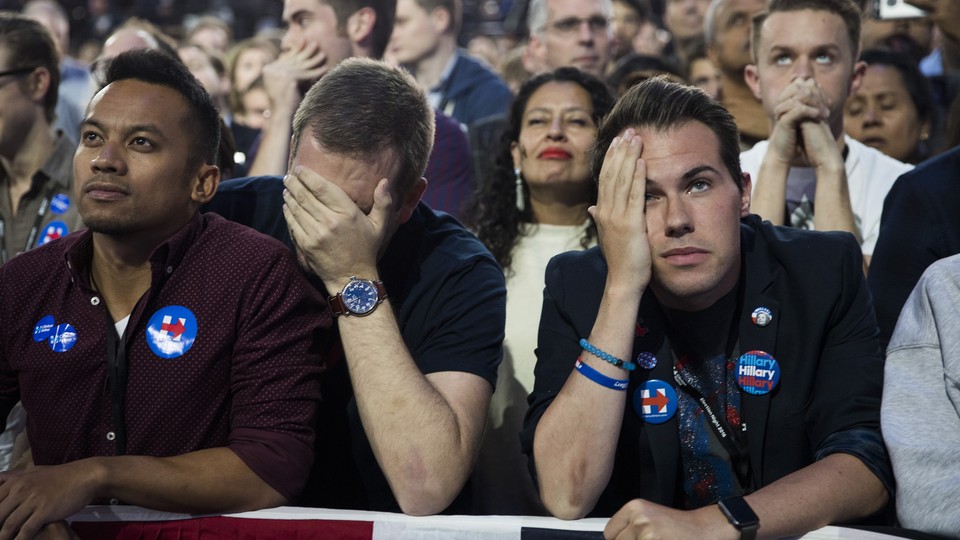

On election night in her home in Chicago, she invited friends over and told them all to bring champagne. As state after state flipped to red, her friends left quietly, one by one. Caffrey yelled at her husband for being too confident Hillary Clinton would win. She blamed herself for not volunteering more. Then she cried herself to sleep, “thinking about all the people who would die and suffer and become fearful and hated and hateful unnecessarily under a Trump presidency.”

Tony Doran, a married gay man from New Jersey, was on a tropical vacation when he heard the news. “I left the luau and went back to our room and cried,” he said. “I was physically sick with terror.”

In Kentucky, it took Christine Tran a full week before “Trump is president” was not her first thought upon waking up in the morning.

Stephanie Delgado-Garcia had volunteered for Clinton in Pennsylvania and went to vote with her formerly undocumented immigrant parents. She took a picture of her mother wearing a Hillary button in the voting booth. “I felt like I lost my country that night,” she said. “Here was a man who essentially told the American public that the America I thought was great was in fact broken for making my story possible,” she said.

It’s now months later, and Caffrey, like many others, still feels “overwhelmed with despair.” Her feelings are familiar to many liberals, to whom political news resembles a multi-car pileup that it’s impossible to look away from. (I found Caffrey and other Trump opponents through my extended online network. Some of those quoted here are acquaintances and others are strangers.)

Even months after the election, these Trump opponents report feeling chronically sad and unrelentingly angry, signaling a major shift in the mental state of a substantial portion of the country. About half of Americans tell pollsters they disapprove of Trump, but for some, the “disapproval” borders on clinical depression.

I’ve never felt worse for such a long time and I say that as someone whose bed was once a foam chair rescued from a trash fire in Hollywood.

— Choire (@Choire) February 16, 2017

It’s easy to mock reactions like these, but for liberals and conservatives alike, losing at the polls can produce an all-encompassing sense of despair. Conservatives experienced something similar after the election of Obama, whose socially liberal platform was anathema, for example, to many religious people.

As Senator John McCain conceded to Obama in 2008, Kevin Neugebauer of Katy, Texas, told CNN he was “distraught” and struggling to understand “how it could happen.”

And in 2012 Mitt Romney supporter Marianne Doherty of Boston told the Washington Examiner, “It makes me wonder who my fellow citizens are. I’ve got to be honest, I feel like I’ve lost touch with what the identity of America is right now.”

Today, Trump supporters are rejoicing, especially as Trump has shown that he was serious about the policy proposals he seemed to ad-lib on the campaign trail.(Strangers in Their Own Land is actually the title of a book by Arlie Russell Hochschild about the grievances of conservative Americans.)

“We are jumping up and down saying, finally we got someone in there who is rooting for the everyday, hard-working American,” said Steve Bentley, a retired man I met in a Lowes hardware store in Elizabethton, Tennessee, recently.

Liberal hand-wringing about Republican administrations is also not historically unprecedented, as Zachary Karabell, an author and investor, recently pointed out in The Washington Post. “One Cornell activist and supporter of incumbent Democrat Jimmy Carter spoke for millions when he said Nov. 5, 1980: ‘The election of Ronald Reagan is a disaster for the country because he’s a fascist,’” Karabell wrote. “I can vividly remember my high school history teacher walking dazed through the corridors convinced that the end of the republic was at hand, a phrase he muttered throughout the coming days in dead seriousness.”

Still, Trump’s outlandish personality has heightened the ideological animus Democrats would have felt toward any Republican president. Antagonism toward George W. Bush was severe, but this feels, well, different. A gym in Scranton, Pennsylvania, had to ban cable news from its TVs after “several locker room and gym disputes over politics and news turned so heated that some members feared for their safety,” as McClatchy reported.

“I always felt that Bush thought he was doing the best thing for the country,” said C.L. Beerman, an attorney in Columbus, Georgia. “I feel as if Trump is only doing what's best for himself.”

The feeling is perhaps most acute among young liberals, who have enjoyed an executive branch broadly aligned with their views for the majority of their adult lives. “The last eight years have been what we thought life was like,” said Peter Corbett, the millennial founder of iStrategyLabs.

I feel like America is that product you thought you could “set it and forget it” and now we’re realizing it breaks down all the time

— Heidi N Moore (@moorehn) February 17, 2017

Some of the Trump-anguish manifests as wishful thinking. Social media brims with impeachment fantasies, and there’s an entire website devoted to an alternate reality in which Hillary won. Some people unplug: In Bend, Oregon, Mark Green has had to stop talking about the news at home, finding it makes him unable to “shut up about how we're all doomed.” They start to question normal life events: Emily Michaels, who is pregnant, said she feels morally conflicted about bringing another child into the world. Caffrey, meanwhile, has taken a proactive approach: She watches PBS Newshour, programmed her representatives’ phone numbers as “favorites” in her phone, and tracks her progress with the calling system 5calls.org.

“I also let myself feel the outrage and sadness,” she said. “I like to think it keeps me strong.”

Delgado-Garcia works as an attorney at a nonprofit that provides free legal services to unaccompanied minors. “Now on an almost daily basis I have to tell teen rape survivors, former gang targets, and other children in equally terrible situations that I really don't know what Trump will do next,” she said. “My clients now ask when and not if they will get deported to face their abusers again.”

It’s all made her question “just how American I really am,” she said.

Whiplashing from feeling proud of America to no longer recognizing it—all while still being an American—can provoke a well-known psychological phenomenon called cognitive dissonance, or stress from experiencing conflicting beliefs.

Tran, for example, said “It makes me question my sanity if something so apparently wrong to me, seems like the truth to someone else.”

Several studies have shown that when two identities—like, say, American nationality and a liberal worldview—are no longer compatible, it can provoke “neuroticism, depression, and anxiety.”

What’s more, pride in one’s nation has been shown to boost happiness and well-being, according to a study by Tim Reeskens of the Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium, and Matthew Wright of American University. The president shapes how citizens and outsiders view a nationality—as liberals who traveled to Europe during the “freedom fries” era of the Bush administration can attest. “Great leaders can define the group and even influence the identity of people who join the group long after they're gone,” said Jay Van Bavel, an associate professor of psychology at New York University.

In other words, the Great Liberal Depression is fairly understandable: Trump helps define what people think of America, and if they feel ashamed of it because of him, their levels of “subjective well-being” will inevitably decline.

“Feelings of helplessness can lead to depression and hopelessness,” Van Bavel said. “I suspect that many people will be looking at four years of this feeling.”

Events that spark anxiety and fear—like Trump’s election did for liberals—can prompt a need for “cognitive closure,” a term coined by University of Maryland sociologist Arie Kruglanski to describe the need for a plan of action that allows a person to put the adverse event behind them. As Kruglanski told me, many liberals are demonizing Trump supporters at the moment because of a need for this kind of closure.

The liberals I interviewed regarded Trump supporters with a mix of pity, guilt, and anger. Tran doesn’t “understand how an intelligent person can continue to support him.” Caffrey longs to hold “a long, calm conversation with them where we could look up real information and facts”—though she realizes this sounds a little patronizing.

Doran, the gay man, said the election made him think many Americans don’t prioritize “my safety as a member of a marginalized class of people,” at the ballot box, “and that hurts.”

But closure can have an activating side, too, Kruglanski told me. After we’re done demonizing the other side, for lack of a better word, we go about resisting them.

Wright said one way to re-route the Trump depression is to turn it into action. “You have a disaffected mass of people,” he said. “The question is whether that will get translated into anger that will turn into political change, or if people will disengage.” (The Tea Party provided a similar function for disaffected conservatives in the wake of Obama’s first electoral victory.)

However strongly felt, liberal angst may not lead to political change. The midterms are still two years away—a long time to keep speed-dialing Congress—and the Democrats don’t have a clear leader right now. And yet, they are really freaking angry.

Several people told me they’re coping by becoming activists in their hometowns, putting up posters or helping communities they think will be hurt by Trump. In that way, “The Resistance” can become a new identity, like the Tea Party, which helps Trump-haters reconcile their American pride with their disgust at American leadership.

“Sometimes I tell myself that our country needed the Trump effect to light a fire under liberals’ asses,” Caffrey said. “But then I think about all the damage Trump has done and I think, ‘No, I still wish he would have never run.’”